- Blog

07/08/2025

Mice, the most commonly used species in scientific research, are sentient animals, and their living conditions directly affect their well-being.

All housing and handling conditions for laboratory mice are inherently stressful for these animals due to handling, restraint, invasive and painful procedures, unnatural environments, social discomfort, cage cleaning, and more (Bailey, 2018).

In SPF and SOPF facilities (Specific Pathogen Free / Specific and Opportunistic Pathogen Free), sanitary requirements further increase stress sources:

This first article focuses specifically on the impact of macro-environmental parameters on the welfare of laboratory mice housed under SPF or SOPF conditions.

A second article will explore this further by examining the factors that modulate these primary parameters.

Macro-environment vs. micro-environment: what is the difference?

The macro-environment refers to the animal housing room. It is distinct from the micro-environment, which refers to the cages (for more on how laboratory mice live, see this blog).

Environmental parameters to be controlled according to European guidelines

According to the 1986 and 2010 directives (European Community Council, 1986; European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010), The following environmental parameters must be controlled: temperature, humidity, light intensity and light–dark cycle, ventilation, noise, and vibrations. Ventilation is not considered a primary parameter here, as air exchange rates and relative pressures act as modulators of other environmental parameters, such as temperature and humidity.

A room temperature suited for humans, not for mice

European guidelines require daily monitoring of temperature, which should be maintained between 20 and 24 °C. This range corresponds more to human thermoneutrality (the temperature range that requires the least energy expenditure) but not to that of mice, which is between 29 and 32 °C. Therefore, mice expend energy to maintain their body temperature.

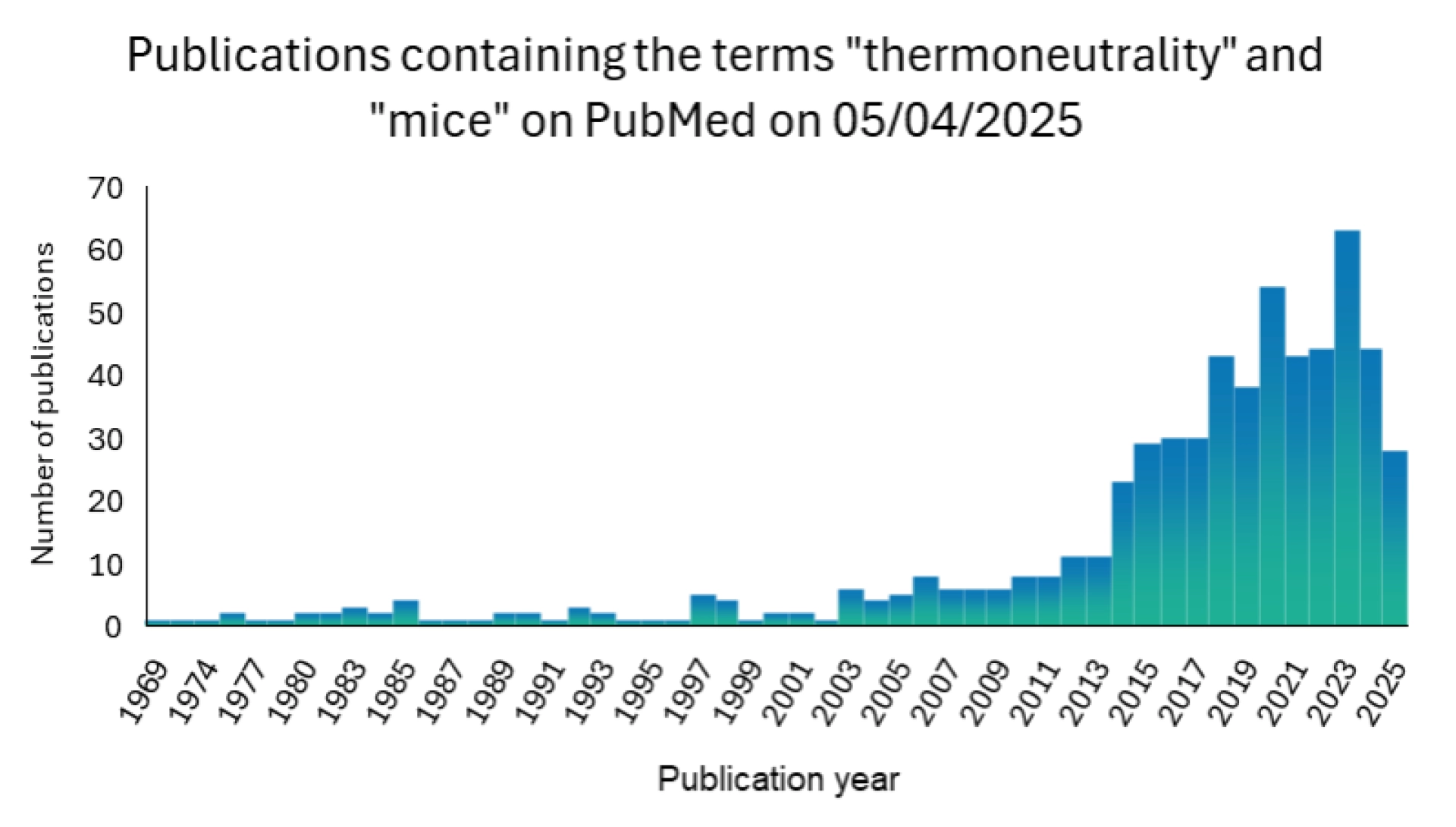

Considering mouse thermoneutrality is a relatively recent development (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Result of a PubMed search using the terms (in “all fields”) “thermoneutrality” and “mice” with the “Other Animals” filter applied, conducted on 11/04/2025.

Physiological and scientific consequences

Temperature affects numerous physiological and pathophysiological functions, including the microbiome, inflammation, cardiovascular system, fat accumulation, bone density, atherosclerosis, tumor growth, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This has become a current topic of interest. Webinars (for example, the FC3R replay “Extrinsic Factors in Animal Research: Temperature and Thermoneutrality” is available here) and scientific reviews highlight the importance of accounting for this bias when using mice to model human diseases (Fischer et al., 2018; Ganeshan & Chawla, 2017; Gordon, 2017; James et al., 2022; Repasky et al., 2024).

Solutions to reduce thermal stress in mice

Increasing evidence highlights the importance of housing mice around 30 °C to improve the translational relevance of studies using these animals.

One approach is therefore to adjust the temperature in housing rooms. However, staff comfort must also be considered. In SPF/SOPF animal facilities, sanitary requirements often necessitate wearing full personal protective equipment, which increases the perceived temperature for staff. More than in conventional facilities, this approach is therefore rarely implemented.

Enriching mice, particularly with items that allow them to build nests, helps them better regulate their body temperature and reduces aversion to colder environments (Garner et al., 2011, 2018; Hylander & Repasky, 2016).

In addition to providing nest-building materials (cotton, kraft paper, shelters), housing mice in stable social groups aids thermoregulation. Mice can sleep together, thereby reducing thermal stress.

Heated platforms can also offer a solution, allowing mice to stay within their thermoneutral zone without altering the room temperature, preserving staff comfort. These platforms were initially developed to improve post-surgical recovery but can also be used in studies particularly affected by thermal stress.

Several models exist: heated cabinets where cages are placed inside (one example), and more conventional racks integrating heating plates under each cage (one example).

Parameters to monitor

The relative humidity of housing rooms must be monitored daily (European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010) and should be maintained between 40 and 60% (Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2019) / 55 ± 10% (European Community Council, 1986).

Relative humidity in cages depends on the room’s humidity, but also on numerous factors such as the number of animals per cage, cage cleaning frequency, type and amount of enrichment and bedding, cage type, cage position on the rack, and ventilation frequency (Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2019).

Risks of too low or too high humidity

Too low humidity can cause dehydration in young animals (Hessler & Leary, 2002) and alter tear secretions, leading to clinical signs of dry eyes (Barabino et al., 2007). Respiratory infections may also occur (Recordati et al., 2015).

Conversely, too high humidity impairs animals’ thermoregulating and increases ammonia levels (due to bacterial proliferation) (Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2019).

Solutions to control humidity

Relative humidity should be constantly monitored, which is generally done at the room level. Since many factors affect cage-level humidity, it is important to watch for clinical signs (e.g., conjunctivitis, respiratory issues).

To monitor humidity inside cages, ventilated racks provide a general indication as the outgoing air humidity is measured and typically displayed. However, cage placement within the rack can cause variation. Miniature weather stations can also be installed in cages (in the feeder for medium-term measurements; directly on the bedding for spot measurements). These precise readings can help explain the appearance of clinical signs.

If ammonia levels in cages are too high (above 25–50 ppm depending on the selected standards (Rosenbaum et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2009)), humidity can be lowered to 30% to adjust ammonia levels, which remains acceptable for mice (Canadian Council on Animal Care, 2019).

Why is light a critical factor?

Light intensity, typically measured in lux, and light-dark cycles are other essential parameters to control in housing rooms, as they can affect the physiology, morphology, and behavior of animals (European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010).

The guide used by AAALAC (for more on AAALAC accreditation and the role of this international association, see this blog ) states that light-sensitive animals should be housed at an intensity of 130–320 lux measured at cage level (European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010).

Light cycles are most often divided into two equal periods (12 h : 12 h). As nocturnal animals, mice are awake during the dark phase and sleep during the light phase. To facilitate staff work, the light phase is often scheduled during the day. Consequently, animals are disturbed, observed, and handled during their sleep phase.

Risks of inadequate lighting

Excessive light can damage the retina, particularly in albino strains. The intensity required to cause physiological damage depends on several factors, including the animals’ usual housing light levels, age, and strain.

No consensus exists on a maximum allowable light intensity in housing rooms. Rodents show a preference for low light levels up to 25 lux (European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010). However, such low levels do not allow staff to work comfortably and hinder the observation of animals in their cages.

It is therefore necessary to set the lowest light intensity that still allows staff to work effectively.

Light adaptation solutions for mice

If light intensity cannot be reduced due to room organization or other factors, enrichment items (such as opaque tunnels) can be used to allow animals to avoid exposure to light (European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, 2010).

At TransCure bioServices, the animal welfare committee has set a threshold of 60 lux at cage level, with an annual audit ensuring compliance.

When handling and observing animals during their sleep phase is too restrictive for achieving the scientific objective (e.g., certain behavioral studies require work during the animals’ active phase), the light-dark cycle can be reversed. In this setup, mice are housed in a dark room during the day, allowing handling during their active phase (see diagram below).

To allow staff to work during standard hours, red light can be used. However, red light affects mice activity and should not replace the dark phase (Hofstetter et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2017).

Role of air handling units (AHU)

SPF and SOPF animal facilities require a controlled environment to maintain high sanitary standards. Air handling units (AHU) allow control of relative pressures between rooms, air exchange rates, as well as humidity and temperature.

Ventilated racks use room air to ventilate cages. Relative pressures between cages and the room are maintained through the air exchange rate in the cages, and the humidity and temperature of the incoming and outgoing airflow are typically displayed for continuous monitoring.

The outgoing air from the rack canbe directed either back into the housing room or outside.

Impact on the microenvironment

Room-level ventilation affects cage ventilation as it modulates temperature and humidity (and consequently CO₂ and ammonia levels), which are parameters that can influence animal welfare (see above).

A malfunctioning AHU or incorrect configuration (particularly of relative air pressures) can pose a sanitary risk, potentially compromising the health of housed animals.

Why is noise a major stress factor?

Noise affects mice used for scientific purposes. This is especially important to consider because mice cannot escape this nuisance in their living environment (making resilience mechanisms compromised) and because these nocturnal animals experience greater disturbance during their sleep phase.

The scientific community has long shown that noise can affect numerous behavioral and physiological parameters, potentially impacting scientific results. Prolonged exposure of mice to high-intensity noise within their hearing spectrum can, in particular, have teratogenic effects and impair reproduction (Peterson, 1980).

Good practices

Sound levels in housing rooms should be minimized, especially high-frequency (or ultrasonic) noises such as whistles generated by faulty motors or female laughter.

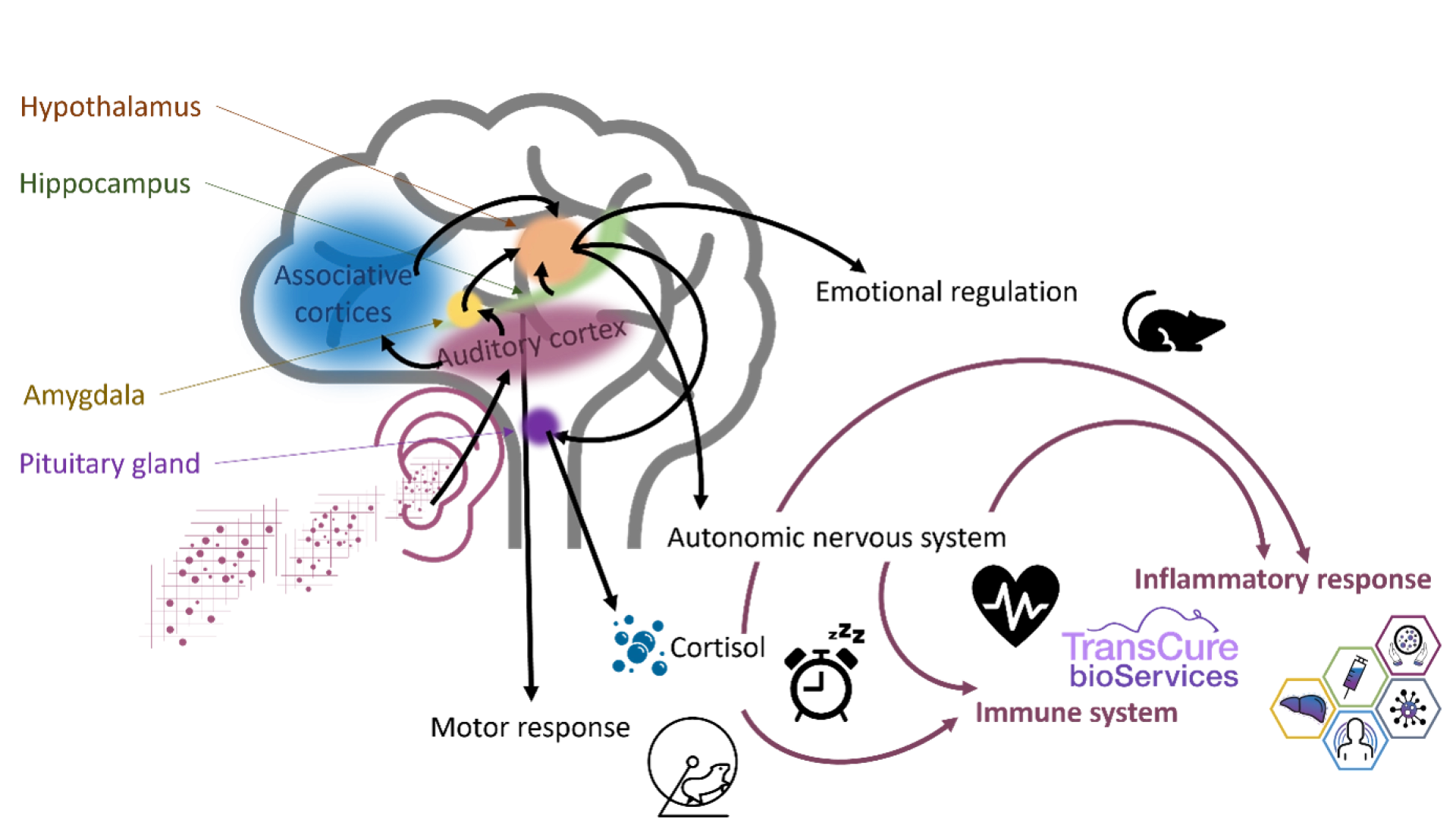

Below is an illustration of the connections between the auditory cortex and other brain structures, impacting many physiological functions.

For more information on this topic, you can consult the dedicated article: Mouse laboratory housing rooms: a focus on noise.

Measurement and recommended thresholds

There are different units to quantify vibrations: amplitude measured as RMS (root mean square), or acceleration in g or m/s², which can be measured along all three axes or only the vertical axis. Measurement tools should cover an appropriate frequency range (2 Hz–500 Hz).

Vibrations are considered a source of stress for laboratory animals and a potential bias that can affect experimental results (Norton et al., 2011; Reynolds et al., 2018).

Vibrations are partly inherent to each facility and housing condition and can originate internally (equipment such as ventilated racks) or externally (e.g., roadworks near the facility).

A threshold of 25 milli-g, based on a literature review, was proposed in 2020, particularly for the impact of vibrations on corticosterone levels (stress hormone) (Turner, 2020). Recommendations suggest minimizing vibrations as much as possible (Fawcett, 2012).

Effects of excessive exposure

Excessive vibrations have been associated with biochemical and reproductive changes in laboratory animals (Briese et al., 1984; Carman et al., 2007). Behavioral effects and changes in corticosterone levels have been observed in mice exposed to 25 milli-g vibrations. Animal sleep can also be affected, as well as physiological parameters, particularly in the cardiovascular system (Turner, 2020).

All these effects, if ignored and unquantified, can become a scientific bias.

Solutions to reduce vibrations

The first step is to design an animal facility taking into account internal sources of vibrations (related to equipment) to isolate them as much as possible from housing areas.

Of course, facility design or layout is not always free of constraints. Selecting equipment can be another way to reduce vibrations and, consequently, their impact on animal welfare and scientific results.

Some vibrations cannot be avoided, for example when the source is external to the facility or when construction work is necessary. In such cases, insulating elements can be used (see the anti-vibration mat in the adjacent image), either to reduce vibration transmission at the source (e.g., under a centrifuge) or to reduce the impact of these vibrations on animals (under mouse racks).

At TransCure bioServices, vibrations are regularly measured at animal racks. Anti-vibration mats have been tested to determine their effectiveness under various circumstances. They are placed under racks during construction phases in the facility, significantly reducing the duration of exceeding the 25 milli-g threshold.

Effects on environmental parameters

Housing rooms can contain multiple racks, each holding up to a hundred cages, with each cage housing up to five mice (under TransCure bioServices conditions).

Excessive density in a housing room can lead to changes in environmental parameters:

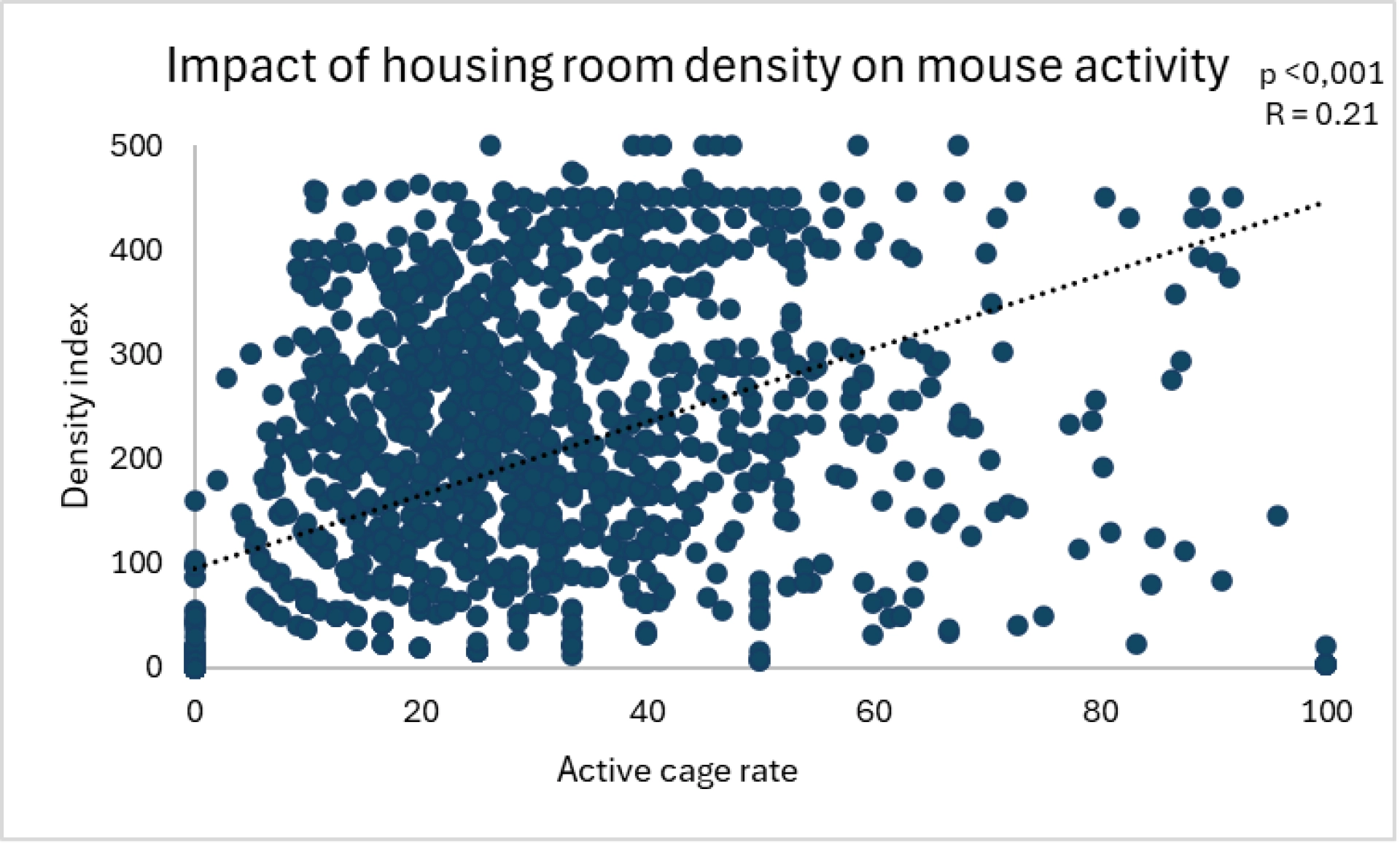

At TransCure bioServices, we focus on maintaining low density in housing rooms, favoring smaller rooms with fewer racks rather than overcrowded large rooms. We have observed a significant positive correlation between a density index (rack occupancy percentage*number of racks) and mouse activity (measured visually using an internally developed method) (see figure below).

Figure 2: Impact of a density index (rack occupancy rate × number of racks in the housing room) on mouse activity. As the data were non-parametric (Shapiro tests), a Spearman correlation was used

Environmental parameters are essential elements to understand and monitor. Their ethical impact can be significant due to their influence on the stress experienced by animals and numerous physiological parameters.

They must also be closely monitored because of the potential scientific bias they may introduce. Indeed, the physiological effects of stress are well established and explain the direct link between animal welfare and data quality. Furthermore, the recent interest of the scientific community in thermoneutrality highlights the importance of paying attention to these factors, which lie outside the scope of the studies themselves.

For more information on housing conditions and animal welfare practices at TransCure bioServices, see our other blog articles.

Bailey, J. (2018). Does the stress of laboratory life and experimentation on animals adversely affect research data? A critical review. In ATLA Alternatives to Laboratory Animals (Vol. 46, Issue 5, pp. 291–305). FRAME. https://doi.org/10.1177/026119291804600501

Barabino, S., Rolando, M., Chen, L., & Dana, M. R. (2007). Exposure to a dry environment induces strain-specific responses in mice. Experimental Eye Research, 84(5), 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EXER.2007.02.003

Briese, V., Fanghanel J., & Gasow, H. (1984). Effect of pure sound and vibration on the embryonic development of the mouse. Zentralblatt Fur Gynakologie, 106(6), 379–388.

Canadian Council on Animal Care. (2019). CCAC guidelines: Mice (CCAC, Ed.; CCAC). Canadian Council of Animal Care. http://www.ccac.caACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Carman, R. A., Quimby, F. W., & Glickman, G. M. (2007). The effect of vibration on pregnant laboratory mice. INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings, 1722–1731.

European Community Council. (1986). Directive 86/609/CEE.

European parliament and of the council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. (2010). Directive 2010/63/EU.

Fawcett, A. (2012). Guidelines for the Housing of Mice in Scientific Institutions.

Fischer, A. W., Cannon, B., & Nedergaard, J. (2018). Optimal housing temperatures for mice to mimic the thermal environment of humans: An experimental study. Molecular Metabolism, 7, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2017.10.009

Ganeshan, K., & Chawla, A. (2017). Warming the mouse to model human diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017 13:8, 13(8), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.48

Garner, J. P., Gaskill, B. N., Gordon, C. J., Pajor, E. A., Lucas, J. R., & Davis, J. K. (2018). Impact of nesting material on mouse body temperature and physiology Author’s personal copy Impact of nesting material on mouse body temperature and physiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.12.018

Garner, J. P., Gaskill, B. N., Rohr, S. A., Pajor, E. A., & Lucas, J. R. (2011). Working with what you’ve got: Changes in thermal preference and behavior in mice with or without nesting material Author’s personal copy Working with what you’ve got: Changes in thermal preference and behavior in mice with or without nesting material. Article in Journal of Thermal Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2011.02.004

Gordon, C. J. (2017). The mouse thermoregulatory system: Its impact on translating biomedical data to humans. Physiology & Behavior, 179, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2017.05.026

Hessler, J. R., & Leary, S. L. (2002). Design and Management of Animal Facilities. Laboratory Animal Medicine, 909–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012263951-7/50024-7

Hofstetter, J. R., Hofstetter, A. R., Hughes, A. M., & Mayeda, A. R. (2005). Intermittent long-wavelength red light increases the period of daily locomotor activity in mice. Journal of Circadian Rhythms 2005 3:1, 3(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1740-3391-3-8

Hylander, B. L., & Repasky, E. A. (2016). Thermoneutrality, Mice, and Cancer: A Heated Opinion. Trends in Cancer, 2(4), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2016.03.005

James, C. M., Olejniczak, S. H., & Repasky, E. A. (2022). How murine models of human disease and immunity are influenced by housing temperature and mild thermal stress. https://doi.org/10.1080/23328940.2022.2093561

Lovasz, R. M., Marks, D. L., Chan, B. K., & Saunders, K. E. (2020). Effects on Mouse Food Consumption after Exposure to Bedding from Sick Mice or Healthy Mice. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 59(6), 687–694. https://doi.org/10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-19-000154

Norton, J. N., Kinard, W. L., & Reynolds, R. P. (2011). Comparative Vibration Levels Perceived Among Species in a Laboratory Animal Facility. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animals, 50(5), 653–659.

Peterson, E. A. (1980). Noise and laboratory animals. Laboratory Animal Science, 30(2), 422–439.

Recordati, C., Basta, S. M., Benedetti, L., Baldin, F., Capillo, M., Scanziani, E., & Gobbi, A. (2015). Pathologic and Environmental Studies Provide New Pathogenetic Insights Into Ringtail of Laboratory Mice. Veterinary Pathology, 52(4), 700–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300985814556191

Repasky, E. A., Hylander, B. L., & Mohammadpour, H. (2024). Temperature matters: the potential impact of thermoregulatory mechanisms in brain–body physiology. Genes & Development, 38(17–20), 817–819. https://doi.org/10.1101/GAD.352294.124

Reynolds, R. P., Li, Y., Garner, A., & Norton, J. N. (2018). Vibration in mice: A review of comparative effects and use in translational research. In Animal Models and Experimental Medicine (Vol. 1, Issue 2, pp. 116–124). John Wiley and Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/ame2.12024

Rosenbaum, M. D., VandeWoude, S., Volckens, J., & Johnson, T. (2010). Disparities in Ammonia, Temperature, Humidity, and Airborne Particulate Matter between the Micro-and Macro environments of Mice in Individually Ventilated Caging. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 49(2), 177–183. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42767874_Disparities_in_Ammonia_Temperature_Humidity_and_Airborne_Particulate_Matter_between_the_Micro-and_Macro_environments_of_Mice_in_Individually_Ventilated_Caging

Silverman, J., Bays, D. W., & Baker, S. P. (2009). Ammonia and carbon dioxide concentrations in disposable and reusable static mouse cages. Lab Animal, 38(1).

Sterley, T. L., Baimoukhametova, D., Füzesi, T., Zurek, A. A., Daviu, N., Rasiah, N. P., Rosenegger, D., & Bains, J. S. (2018). Social transmission and buffering of synaptic changes after stress. Nature Neuroscience, 21(3), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0044-6

Turner, J. G. (2020). Noise and Vibration in the Vivarium: Recommendations for Developing a Measurement Plan. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 59(6). https://doi.org/10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-19-000131

Zhang, Z., Wang, H.-J., Wang, D.-R., Qu, W.-M., & Huang, Z.-L. (2017). Red light at intensities above 10lx alters sleep-wake behavior in mice. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.231